|

Vol.3, No 11, October 2010 |

|

If you are having problems viewing this page or the graphics please Click Here to view it in your browser or to visit our Blog Click Here. To view my Galleries of Geo-referenced photos from around the world Click Here. To view additional galleries Click Here. |

|

To remove your name from our mailing list, please click here. Questions or comments? Email us at fhenstridge@henstridgephotography.com or call 951-679-3530 To view as a Web Page Click Here. Please visit our Web Site at http://henstridgephotography.com. © 2009 Fred Henstridge Photography All Photos, Images, Graphics and Text are the copyright of Fred Henstridge Photography. All Rights are Reserved. |

|

I have added an archive of all past editions of the Aperture. You can access this archive by clicking here. |

|

William McKinley (1843-1901) 25th President of the United States (1897-1901) |

|

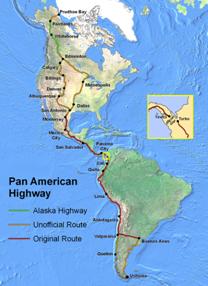

There were, at one time five possible routes for a canal across the Isthmus. Panama and Nicaragua were the popular choices, with many Americans favoring Nicaragua. Click to Enlarge |

|

Theodore "Teddy" Roosevelt (1858-1919) 26th President of the United States (1905-1909. |

|

An example of the Darien jungle along the shores of Gatun Lake, Panama. |

|

The Pan American Highway with the Darién Gap between Panama and Colombia. (Click to enlarge) |

|

Bunau-Varilla's rejected flag design for Panama |

|

Manuel Amador Guerrero (30 June 1833 - 2 May 1909), was the first president of Panama from 20 February 1904 to 1 October 1908 |

|

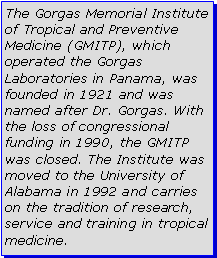

Dr. William Gorgas (1854-1920). As chief sanitary officer on the canal project, Gorgas implemented far-reaching sanitary programs including the draining of ponds and swamps, fumigation, mosquito netting, and public water systems . |

|

John Stevens excavated the Culebra Cut with an ingenious system of rail cars and steam shovels in constant motion. Note the 95-ton Bucyrus steam shovel filling the cars. |

|

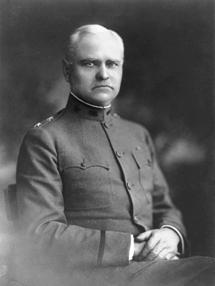

George Washington Goethals ; (June 29, 1858 – January 21, 1928) was the United States Army officer and civil engineer, best known for his supervision of construction and the opening of the Panama Canal . |

|

Marias Pass obelisk and statue of John F. Stevens (Elevation, 5,213 feet) |

|

John Frank Stevens (1853-1943) was chief engineer on the Panama Canal between 1906 and 1908. |

|

In Part One Panama Canal story I addressed some of the technical aspects of the canal and its operation along with my personal experiences while transiting this great engineering marvel. In Part Two I discussed the original Spanish efforts at crossing the Isthmus separating the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans along with the French attempt to build a sea level canal across the Isthmus. You can read either publication by clicking on the appropriate number.

In this final chapter of the Panama Canal Story we will explore the American efforts to build the Canal and what effects it had on medicine, disease control, civil engineering and global politics. |

|

You can view a complete gallery of all the photos I took while on our 15-day Panama Canal Cruise by clicking here. The photos taken during the Panama Canal transit begin at number 336 I hope you enjoy them as much as I did taking them. When you view one of the photos and it has a hyperlink (shown in red) under the caption you can click on it to open a Google Map showing the exact location where the photo was taken. When traveling, I always use a GPS attachment on my Nikon cameras so I can document the position of each photo. |

|

An American Canal

Three weeks after his 89th birthday, Ferdinand de Lesseps quietly died in bed at his country home. The year was 1894 and Theodore Roosevelt, still in his thirties, was on the ascent.

Born into a prominent New York family, raised by nannies and educated by private tutors, Roosevelt travelled widely with his parents before graduating from Harvard and studying law at Columbia. He was an intellectual, an outdoorsman. a conservationist, a reformist, an expansionist, and a fighter.

A man of boundless vitality and enthusiasm, Roosevelt as president would capture the imagination of the American people with his pithy phrases and adamant defense of the rights of the "little man" versus the powerful industrialists. He stood 5' 8" but he was stocky and appeared to be much larger. And he exuded confidence, in his walk, in his talk. Suffering frail health as a child, he led a life of vigorous pursuits, returning home a hero from the Spanish-American war in Cuba where his famous Rough Riders regiment was victorious.

Above all else, Roosevelt believed in military muscle and the importance of sea power if America was to achieve world supremacy — a point sharply illustrated during the Spanish-American war when it took an American battleship two months to reach Cuba, sailing from San Francisco via Cape Horn. It was obvious that a Central American canal must be built. And it must be American built and under American control. And the place to build it, most Americans agreed, was Nicaragua.

Nicaragua had a shining reputation. Not only was it closer than Panama to American shores. Nicaragua was viewed as politically stable and disease-free. The proposed inter-oceanic route would follow a navigable river and the sparkling waters of Lake Nicaragua before reverting to a man-made canal on its Pacific side. Volumes of data from American surveys supported the Nicaragua route, as did the Nicaragua Canal Commission, a presidential study of the best potential route for the canal. And, perhaps most important in the minds of the American public, Nicaragua would be a fresh start, far removed from the "junk heap of Panama" — as veteran Senator John Tyler Morgan of Alabama liked to refer to the abandoned French canal.

In 1899 a second study was ordered by President William McKinley, called the Isthmian Canal Commission but widely referred to as the Walker Commission, for the name of the Admiral who headed its board of eminent engineers. When the Commission's report was released, in November 1901, it contained some surprising recommendations. Based on two years of field work, including trips to Panama and to Paris to view the French canal company’s records and plans, the board maintained that Nicaragua was still the most feasible route.

However, the deciding factor was not an engineering one, but the high price tag the French had put on their canal holdings. Within weeks of the study's release, the new French canal company slashed its asking price from $I09 million dollars to $40 million ($1.07 billion in today’s dollars according to the CPI). A month later the Walker Commission reversed its decision, unanimously supporting Panama as the best choice for an American canal. Money will certainly talk.

How this remarkable about face occurred was due in large part to the behind-the-scenes efforts of two highly effective lobbyists, Philippe Bunau-Varilla and William Nelson Cromwell. Bunau-Varilla, a chief engineer with the original canal company at Panama, was the organizer of the new French company that had taken over the canal rights. He and others, including Gustave Eiffel, were penalty shareholders in the new company, which meant they would have faced fraud charges for the profits they had made from the original canal project had they refused to invest in the new venture. Cromwell, an American, was a high-powered corporate lawyer hired in 1894 by the new canal company to represent its interests, i.e. sell its canal holdings to the United States government.

These two men, working independently and openly disdainful of each other, proceeded to unleash their powers of persuasion and logic on the key American officials who would play a role in deciding where an American canal would be built. Cromwell was simply earning his $80,000 commission, while Bunau-Varilla’s motives were more complex. As a shareholder in the new canal company he certainly had a vested interest in selling its holdings to the United States government, yet he convincingly claimed he was on a mission to resurrect the Panama Canal and restore French glory. The impeccably polite little Frenchman struck Americans as being slightly eccentric with his huge black moustache waxed at the ends into sharp points, but he had a steel-trap mind, a riveting personality and was zealous in his quest to redeem French pride, using whatever means were necessary to achieve his goal. |

|

In early 1901, Bunau-Varilla had embarked on a three-month tour of the United States. Giving speeches and making friends in high places. All along he had focused his efforts on the key players, convincing Ohio Senator Mark Hanna, a powerful industrialist and dominant force within the Republican Party, that Panama was the superior canal route. Bunau-Varilla even paid a visit to the home of the irascible John Tyler Morgan, a vociferous opponent of the Panama route, and their brief meeting almost ended in a punch-up when, baited by Morgan. Bunau-Varilla came close to striking the elderly Senator.

Then, in the fall of 1901, shortly before the Walker Commission released its report, President McKinley was shot by an anarchist and died eight days later. Theodore Roosevelt, at the age of 42, was now President of the United States. The response was far from muted. Upon hearing the news, Mark Hanna, whose political and financial backing had propelled McKinley to the White House, is reported to have said, "Now look! That damned cowboy is President of the United States." Back in Paris, Bunau-Varilla was aghast, for he had not even bothered trying to meet Roosevelt while he was Vice- President. Bunau-Varilla now hurried back to the United States to try and meet with the new Commander in Chief.

The shifts in presidential style were swift and spell binding. Roosevelt, a Harvard-educated New Yorker who enjoyed horseback riding at his ranch in the Dakota Territory, was now the center of his country's attention and he revelled in his new role. He was the first president to call his official residence the White House (instead of the Executive Mansion) into which he moved his large and boisterous family. While distinguished guests arriving for state dinners were gathering in the mansion's public rooms, the President could be found upstairs in the nursery having pillow fights with his children.

Roosevelt’s youthful vigor struck a responsive chord with the American people, yet he was a complex man, whose passion for physical pursuits and outdoor activities belied his scholarly mind. An avid reader and progressive thinker, Roosevelt harbored an intense interest in the 'canal question' and was painstakingly familiar with all aspects of potential canal routes, right down to details on topography. And it would soon become apparent that Roosevelt had changed his mind about where the canal should be built. Like most Americans, he had long favored the Nicaragua route. However, the case for Panama was more logical when based on engineering considerations, namely that the Panama route had better harbors, was shorter, required fewer locks (five versus eight), and its potential problems had already been exposed by the failed French effort. Nicaragua on the other hand was an unknown.

In addition, there was the issue of volcanoes - with no fewer than a dozen located in Nicaragua – a point Bunau-Varilla kept making in his speeches but which no one seemed to take very seriously until May 8. 1902, when Mount Pelee on the Caribbean island of Martinique erupted with such force that a superheated cloud of burning gas blanketed the nearby town of St. Pierre and killed all 30.000 residents but one - a prisoner protected by the walls of his jail cell. Days later, Momotombo in Nicaragua erupted, followed by another explosion of Pelee and a volcanic eruption on the Caribbean island of St. Vincent.

While volcanoes were erupting, the Senate hearings got under way. Morgan delivered a vehement speed against Panama, warning that it was only a matter of time before the United States would be compelled to take Panama by force in order to protect the canal, should it be built there. He did not address the engineering aspects of the two routes, only the political pitfalls of Panama. This was in contrast to the contents of Mark Hanna's speech, possibly the best of his career, in which he convincingly listed the reasons for favoring Panama. Backing his argument were statements by dozens of shipmasters and pilots who would be using the canal, all of whom agreed that the shorter the canal, the better, for the less time spent in a canal meant less risk of damage to their ships. Reiterating the points made by the Walker Commission, Hanna stated that a Panama Canal would have fewer curves, would cost less to run and, most importantly, it was the route the engineers studying the issue recommended - an argument, Morgan had scoffed at earlier, declaring that the Walker Commission's preference for Panama had nothing to do with engineering arguments but with the cheap price the U.S. was being offered for the French company's holdings.

The pending vote in the Senate looked like it could go either way. The American press still supported the Nicaragua route and political cartoonists like to poke fun at the pro-Panama forces’ “volcano scare". Throughout the hearings, the Nicaraguan embassy in Washington steadfastly denied that Momotombo had just erupted, even though it had. In a final pitch, Bunau-Varilla hit on an idea of sending to each Senator the one-centavo Nicaraguan stamp depicting Momotombo in full eruption. Days later, when the Senate vote was held, Nicaragua received 34 votes, Panama 42. A week later the House passed the Spooner Act, which authorized the President to build a Panama Canal. |

|

Mount Pelée on the island of Martinique, famous for its eruption in 1902 and the destruction that resulted killing 30,000 people. Now dubbed the worst volcanic disaster of the 20th century. |

|

Mount Momotombo, Nicaragua, it’s 1905 eruption was used by proponents of the Panama route to dissuade those in favor of the Nicaragua route. |

|

Revolution and Remuneration

When the Spooner Act was passed, by an overwhelming majority in the House on June 26, 1902, the Isthmus of Panama was part of the republic of Colombia, and had been since 1819. That was the year Simón Bolivar became president of Greater Colombia after leading his revolutionary forces across the flooded Apure valley and over the Andes Mountains to defeat a surprised Spanish army in north-central Colombia. After three centuries of exploitation under Spanish colonialism, during which the Isthmus of Panama was ruled first by the viceroyalty of Peru, then by the viceroyalty of New Granada. This strategically located neck of land was for the first time part of an independent nation.

In 1830, Venezuela and Ecuador broke away from Greater Colombia and the remaining country would eventually be called the United States of Colombia. The Isthmus of Panama, although physically separated from the rest of Colombia by the dense Darien jungle, was highly prized by the Colombian government as a source of revenue. Its annual share in the earnings of the Panama Railroad was $250,000, and potential profits from a canal promised to be even more lucrative. Although rich in natural resources, Colombia, like many a former Spanish colony, struggled with self-government. Social and political stability remained elusive, and a revolution in 1885 was followed by the outbreak of a bloody civil war in 1899, which raged until 1904 when internal order was restored. But it was too late for Colombia to save its cherished province of Panama. Through an insurrection sponsored by the United States and orchestrated by Bunau-Varilla, Panama had gained independence from Colombia. It was one of the strangest revolutions the world has witnessed.

It began back in Washington, where negotiations were tediously slow between Secretary of State John Hay and three successive Colombian foreign ministers. The soft-spoken Hay was a man of letters, trained in law and journalism who had served as President Lincoln's assistant private secretary and written several books. He had negotiated the Hay-Pauncefort Treaty in which Britain relinquished to the U.S. the right to build an isthmian canal in Central America. His Colombian assignment seemed straightforward enough. But Hay, the experienced and erudite statesman, was dealing not only with Colombian diplomats whose Spanish sense of pride and decorum were at odds with the “let's get on with it” American approach, but with a cryptic Colombian government which seemed to be continually shifting its position in its instructions from Bogota. The two main issues were Colombian sovereignty and money. Colombia's diplomats in Washington felt they were being bullied by the American administration, which threatened to enter negotiations with Nicaragua if Colombia persisted in delaying a treaty settlement. Dr. Tomas Herran, the multilingual and highly educated Colombian diplomat who cautiously reached an agreement with Hay, spoke in private of Roosevelt’s "impetuous and violent disposition" which might predispose him to taking Panama by force. Hay urged restraint to President Roosevelt, who was becoming increasingly impatient with the Colombians whom he referred to as "jack rabbits" and "those bandits in Bogota”.

The main stumbling block for Colombia was the $40,000,000 the French canal company was to receive from the United States. Colombia wanted to receive a portion of this payment as commission for allowing the transfer of the Canal Zone, but the French canal company did not agree and Cromwell was working hard behind the scenes to convince the American government that none of the agreed-upon purchase price should go to Colombia.

Eventually a treaty was drawn up and signed in Washington by Hay and Herran, which granted the United States control of a canal zone six miles-wide between Colon and Panama City, and which authorized the French company to sell its Panama holdings to the American government. In return, Colombia would receive a lump sum of $10,000,000 and. after nine years, an annuity of $250,000. The treaty's terms were not popular with Colombians, who believed they should be receiving more financial compensation, and the Colombian Senate refused to ratify the treaty.

While Colombia equivocated, Panama conspired. A small group of prominent Panamanians began planning a revolution, led by 70-year-old Dr. Manuel Amador who, although born and educated in Cartagena, had lived in Panama since the California gold rush of 1848. The leaders of the movement all worked for the Panama Rail Road and were in contact with Cromwell. These included Jose Agustin Arango, the railroad's attorney and a Panamanian senator, and the assistant superintendent Herbert Prescott, an American. In August 1903, Dr. Amador boarded a steamer bound for New York to drum up American support for their insurrection.

An intrigue of secret meetings and coded messages unfolded during Amador's stay in New York. Double-crossed by a Panamanian businessman he had met while playing poker on the sea voyage to New York. Amador found himself getting nowhere with his American contacts until Bunau-Varilla arrived from Paris and, with characteristic efficiency, began organizing Amador's revolution down to the minutest details, including the first draft of a Panamanian declaration of independence and a new flag his wife had quickly stitched together.

While Amador waited in New York. Bunau-Varilla hurried by train to Washington where he was able to meet with Roosevelt and engage in an oblique conversation concerning a possible revolution in Panama. By the end of their meeting, Bunau-Varilla was convinced Roosevelt was prepared to support an insurrection. Back in New York, in his final briefing with Amador, Bunau-Varilla insisted the revolution take place on November 3 and provided the text for a telegram to be sent once the junta gained power, confirming Panama's independence and authorizing Bunau-Varilla to sign a canal treaty with the U.S,

When Amador returned to Panama, his cohorts didn't like the new flag and were nervous about staging a revolution based on the assurances of an unknown Frenchman. One influential member of the junta, claiming he was too young to be hanged, threatened to back out unless there was a tangible sign of support from the United States, namely an American man-of-war standing offshore. No one, not even Bunau-Varilla, was entirely sure of Roosevelt’s intentions at this point, but a pending revolution in Panama seemed to be that year's worst-kept secret and anyone monitoring the situation would have noticed a small item in The New York Times reporting that the U.S. gunboat Nashville had sailed on the morning of October 31 from Kingston. Jamaica, its destination believed to be Colombia.

In the end, no fewer than 10 American warships would converge on both sides of the Isthmus, and it was undoubtedly their presence that decided the fate of Panama. In the meantime, it was the Panama Railroad and its superintendent. a 70-year-old American named Colonel James Shaler, who saved the day for the junta when a Colombian warship Cartagena arrived at Colon only hours after the Nashville showed up on November 2. Commander Hubbard of the Nashville was there under the pretext of maintaining free and uninterrupted transit of the Panama Railroad, so he did nothing to Stop General Tobar, the Colombian commander, from landing five hundred troops the next morning.

It was at the railroad wharf that the stonewalling began by Shaler, who had been notified of the troops' pending arrival and had shunted railcars away from the station. General Tobar and his senior officers suspected no hanky-panky when Shaler suggested they board a special car for Panama City, leaving their troops behind in Colon until more railcars were available. Away went Tobar and his officers, heading straight for a trap that was being set in Panama City, where a small garrison of Colombian troops was stationed. These soldiers had not been paid for months and their commanding officer, General Huertas, was known to be sympathetic to the revolutionary movement. So, when approached by Amador and offered a small fortune if he joined the revolution and arrested Tobar, the young general reportedly hesitated for about a second before accepting the offer.

Back in Colon, a confidential telegram arrived for Hubbard, instructing him to prevent the landing of Colombian troops. Meanwhile Shaler was using delay tactics to prevent the movement of these same troops, insisting their fares be paid in full and in cash before they could ride on the rail road. At the other end of the line, Panama City buzzed with anticipation of an uprising slated for 5:00 p.m. in Cathedral Square, General Tobar and his officers, enjoying a fine lunch at Government House, still suspected nothing. But when his troops failed to arrive by mid-afternoon, Tobar began to grow anxious.

As a crowd gathered in front of the military barracks, and an unsuspecting Tobar and his officers conferred on a bench near the gate to the seawall, Huertas issued the order. Armed with fixed bayonets, a company of soldiers marched out of the barracks and surrounded the seated general and his officers, demanding their surrender, which they did after beseeching some of the nearby sentries to come to the defense of their country. None came to their aid, and they were marched to the local jail.

While a jubilant crowd celebrated the success of their revolution in Cathedral Square, back in Colon the Colombian troops, under the command of a young colonel named Torres, were still trying to catch a train to Panama City.

At noon the following day, over a drink in the Astor Hotel saloon, a Panamanian named Melendez told Torres what had happened the day before in Panama City. Torres flew into a rage and threatened to burn the town and kill all Americans if the Colombian generals were not released. No one took this threat idly, and after sequestering the town's American civilians to ensure their safely, Hubbard landed an armed detachment of sailors who barricaded the railroad’s stone warehouse. He also moved the Nashville closer to shore, its decks cleared for action and its guns trained on the railroad wharf and on the Cartagena, which to everyone's surprise suddenly steamed out of the harbor.

A tense few hours followed as the Colombian soldiers surrounded the warehouse, but no shots were fired and Torres eventually marched his troops to Monkey Hill (also called Mount Hope) where they camped for the night. The next day, driven off by mosquitoes, the Colombian troops marched back into town and Torres agreed to evacuate Colon in exchange for $8,000 which was paid in twenty-dollar gold pieces from the railroad company's safe. By evening he and his troops had boarded a Royal Mail steamer bound for Cartagena.

With the dispatch of Colombian troops and the arrival of more American gunboats at Colon and Panama City, all that remained was for the new Republic of Panama to sign a treaty with the U.S. According to the agreement reached between Amador and Bunau-Varilla in New York, the latter would have the diplomatic powers to act on behalf of the new nation, and act he did. in spite of receiving new instructions not to proceed until a small delegation led by President Amador arrived from Panama.

Bunau-Varilla hurriedly revised the treaty Hay had drafted, making the conditions so favorable to the U.S. — including perpetual control of a 10-milewide canal zone — it couldn't possibly be rejected in the Senate. When the Panamanian delegation stepped off the train in Washington and were told by Bunau-Varilla that he had just signed a treaty on behalf of the Republic of Panama, one of the delegates responded by striking the Frenchman across the face.

Panama had to be content with the treaty and it was not such a bad deal for a new nation, starting out debt free, with a $10,000,000 surplus in the government coffers, guaranteed annual revenue from its railroad and canal concessions, and the security of U.S. naval protection. Colombian troops did attempt to regain their lost province with an overland march through the Darien jungle but had to turn back. The loss of national income for Colombia, already burdened by a costly civil war, was crippling.

Panama's swift secession from Colombia was achieved without bloodshed, but Roosevelt was accused of acting impulsively in his "sordid conquest" of Panama. Roosevelt vehemently defended himself, claiming later in his autobiography that it was "by far the most important action I look in foreign affairs" and totally justified in the interests of national defense. Depending on a person's point of view, it had been gunboat diplomacy at its best, or its worst, tarnishing U.S. relations with Latin America for years to come. The mood of the American public was generally in favor of Roosevelt's actions, especially when Colombia made a desperate attempt following the revolution to accept the terms of the Hay-Herran treaty, proof in many peoples' minds that Roosevelt was right when he accused the Colombian government of extortion. The American President had, in his own words, "taken the Isthmus" and it was time now for the U.S. to make the dirt fly and build that damn canal. |

|

The World's Largest Construction Job

When the United States took possession of the canal works in Panama on May 4, 1904, the scene was, at first glance, one of rot and despair — abandoned and rusted machinery, dilapidated buildings, and filthy towns. On closer inspection, however, the amount of excavation already completed by the French was impressive, much of the equipment was salvageable, and many of the buildings could be refurbished.

Nonetheless, organizing the manpower and supplies needed to bring order and efficiency to the Canal Zone was a gargantuan task, made even more daunting by the establishment in Washington of the Isthmian Canal Commission which had to approve all requisitions received from Panama. It was headed by Walker, whose passion was to make sure no graft tainted the American effort in Panama. As a result, the first Chief Engineer appointed to Panama. John Wallace was as bogged down in red tape as he was in mud. On top of these administrative frustrations was the weight of American public opinion, which wanted to see "the dirt fly" in Panama, prompting Wallace to commence digging right away at Culebra Cut.

There seemed to be no master plan in place, and morale among the workers, already low, plummeted with the outbreak of yellow fever. Panic swept the Isthmus and people couldn't leave fast enough. Even Wallace fled, under the pretext that he had important business to discuss with Secretary William Taft in Washington. Wallace was fired and a new man was quickly found to turn things around in Panama. That man was John Stevens who, at age 52, was widely considered the best construction engineer in the country. Self-educated, Stevens had learned surveying on the job, working his way from truck hand to chief engineer. He was gruff, physically tough and a legend among railroaders for discovering, in the dead of a Montana winter, the Marias Pass over the Continental Divide. When Stevens met with Roosevelt, the two men hit it off immediately and the new Chief Engineer was told to do whatever was needed in Panama, which the President called a "devil of a mess."

It took Stevens, upon arriving in Panama, less than a week to assess the situation. A hands-on and approachable man, he spent hours walking the Canal Zone, in any kind of weather, observing every detail and asking questions. He said little, just looked and listened. Then, six days after his arrival, on August 1, 1905. Stevens ordered all digging stopped. He had determined that the equipment left behind by the French was not large or heavy enough, and the undersized railroad so inefficient it was astounding how much had been accomplished. But the first problem to deal with, in Stevens’ view, was the overriding atmosphere of fear due to yellow fever and other diseases plaguing Panama. Already at hand was the man best qualified to rid the Isthmus of the dreaded yellow fever, namely Dr. William Gorgas — a leading disease and sanitation expert who had rid Havana of yellow fever when sent there with the Army in 1898. Gorgas had been trying to replicate this success since his arrival in Panama a year earlier but with limited results. Few people, including members of the ICC, believed in the “mosquito theory”. To spend thousands of dollars chasing mosquitoes seemed a waste of money to General Walker, who had refused to provide the resources Gorgas had repeatedly requested.

Stevens too was skeptical of the mosquito theory, but he had faith in Dr. Gorgas and he threw the weight of the engineering department at the doctor's disposal. Fumigation brigades, armed with buckets, brooms and scrub brushes, marched on Panama City and Colon where every single house was cleaned and fumigated. Sources of standing water, such as cisterns and cesspools were oiled once a week and both towns were provided with running water, eliminating the need for fresh water containers. The results were immediate. The yellow fever epidemic ended within a month and, although it would take time for Panama to shed its reputation as a death trap, the tide was slowly turning. Malaria was also brought under control as brigades were dispatched to burn brush, dig ditches, drain swamps and clear the areas around the settlements being built along the canal route. The malaria-transmitting Anopheles mosquito is susceptible to strong sunshine and wind, so the cleared areas around the new towns were kept continually clipped and trimmed.

The key to successfully building the canal, Stevens had concluded, was the rail line. Not only was it a lifeline, transporting the needed manpower, machinery and supplies back and forth across the Isthmus, it would be the conveyer belt needed to haul away the huge amounts of dirt to be dug at Culebra Cut. His was not a complicated task, he claimed, but challenging for the massive scale of excavation required. So with a workable plan laid out, the man who had built railroads spanning hundreds of miles of rugged northern terrain now focused his talents and tenacity on a narrow, 50-milel-ong jungle corridor, and the transformation was nothing less than extraordinary.

Stevens brought in experienced railroad men from across North America and proceeded to completely overhaul the existing rail line, installing heavier rails that were double-tracked and equipped with cars that were four times the size the French had used. He also recruited conductors, engineers and switchmen to operate the new rail line, while thousands of tradesmen and laborers were put to work building towns alongside it. A cold storage plant was built at the Cristobal terminal and fresh food, arriving by steamship from New York, was distributed via the rail line, as were fresh loaves of bread from the new bakery. |

|

Stevens was not just building a canal but a modern industrial state in the middle of an isolated tropical wilderness, and a complete infrastructure had to be put in place before the Canal itself could be built. This mammoth undertaking required both skilled tradesmen and unskilled laborers, and six months after his arrival Stevens had tripled the size of the labor force. A year later, by the end of 1906, nearly 24,000 men were working on the Isthmus. The labor force came from all parts of the world, but the majority of skilled white workers were American, representing forty different trades and specialties — from carpenters and bricklayers to cooks and plumbers. Many of the unskilled laborers were from the West Indies, specifically Barbados, where men lined up for the chance to go to Panama and earn a dollar a day.

In early 1906, Stevens resumed digging at Culebra Cut, where he had devised an ingenious system of rail tracks which kept the steam shovels in constant motion as loaded dirt trains rolled out and a steady stream of empty cars rolled in. There was still no official decision regarding the type of canal he was supposed to be building, but Stevens had made up his own mind after watching the Chagres River flood its banks during the rainy season. He firmly believed a sea-level canal would be a "narrow tortuous ditch" plagued with endless slides and ships running aground in the shallow channel, whereas a lock canal could harness and utilize the floodwaters of the Chagres River, creating a freshwater lake that would form a section of the canal and provide water to the locks. Stevens was summoned to Washington to lobby on behalf of a lock canal, and on June 19, 1906, the Senate voted by a narrow margin to build a lock canal .

Everything was now coming together, and in November of that year Roosevelt paid a visit to Panama, the first time a serving president had left the country while in office. Unlike de Lesseps, who twice visited Panama during the dry season, Roosevelt purposely planned his visit during the rainy season so he could experience Panama at its worst. Eager to see everything, Roosevelt set a pace that left Stevens and everyone else exhausted. His infectious enthusiasm was undampened by the driving rain as he cheerfully waved to bystanders from the back of his train and made impromptu speeches whenever the occasion presented itself. At one point, while touring the Cut, he climbed into the driver's seat of a 95-ton steam shovel where he was obviously delighted to be sitting at the controls while the engineer explained how it worked. He was always on the go and often not where the official schedule said he should be. On one occasion, he and his wife were expected at a formal luncheon in the Tivoli Hotel but they instead walked unannounced into one of the employees' mess halls and sat down to a 30-cent lunch.

No sooner did an exuberant Roosevelt return to Washington, confident of success in Panama, when a fly appeared in the ointment. Stevens, who had won Roosevelt’s full confidence, was showing signs of cracking under the pressure. Suffering from insomnia, Stevens wrote what was interpreted as a letter of resignation to Roosevelt in late January 1907, just as the French chief engineers had complained of the "disorder of detail", Stevens now spoke of the tremendous responsibility and strain he was under due to "the immense amount of detail." These complaints were likely not too startling to Roosevelt, but further along in the letter came the clincher, wherein Stevens refers to the canal, Roosevelt's "future highway of civilization", as "just a ditch" and one of questionable utility at that.

Stevens, who dreaded ocean voyages due to his seasickness, did not share Roosevelt's passion for naval supremacy and seagoing trade, but his personal reasons for resigning were never disclosed. Most observers concluded that the man was, quite simply, worn out. As for Roosevelt, he was profoundly disappointed in Stevens for his lack of commitment and sense of duty. To insure that the next man in charge of building the canal stayed on the job, Roosevelt declared he was turning the work over to the army, to a corps of elite engineers trained at West Point Military Academy, its curriculum patterned after that of France's prestigious Ecole Polytechnique. These were engineering officers instilled with an honored tradition of serving their country. For them, the option of quitting was unthinkable.

The man Roosevelt appointed as chief engineer and chairman of the canal commission was a 48-year-old colonel named George Goethals. Born in New York of Flemish parents, Goethals was a model officer and specialist in coastal defenses. The line of authority in Panama had been streamlined at Stevens’ request, and Goethals was now supreme commander of the Canal Zone. It quickly became apparent that he was a leader of unbending standards. His efficiency and command of details was unsurpassed, but he lacked the warmth and colorful personality of Stevens, whose departure from Panama was marked by a crowd of workers waving and cheering and singing Auld Lang Syne as his steamer pulled away from the pier at Cristobal . |

|

Goethals had big shoes to fill and his first months in Panama were lonely. his evenings spent writing long letters home to his son who was in his senior year at West Point. Goethals soon earned the respect if not the affection of the canal workers and, despite his stem manner, was regarded as a benevolent despot by holding, each Sunday morning, a court of appeal in his office where workers could voice their grievances and requests while he listened patiently. His decision on each matter was final and few questioned his authority.

Goethals also started a weekly community newspaper, called the Canal Record, which boosted morale and tied the settlements along the rail line together. Weekly excavation statistics for the teams operating the steam shovels and dredges were published, prompting an ongoing competition to capture that week's record. A healthy rivalry was also inspired by Goethals’s reorganization of departments into three geographic units, with army engineers assigned to the Atlantic Division (handling design and construction of the Gatun Locks and Dam) and civilian engineers responsible for the locks and dams of the Pacific Division on the other side. The 31 miles of canal in between were called the Central Division, comprised of both army and civilian engineers, whose major challenge was the nine-mile stretch of the Culebra Cut. Stevens had laid the foundations for building the canal, but engineers with expertise in hydraulics and the large scale use of concrete were now needed to construct the colossal locks and dams, and their work would prove to be outstanding.

The American public, and the world at large, was fascinated with the canal's construction and tourists arrived by the shipload to view the proceedings. The biggest attraction was the Culebra Cut, where men in straw hats and ladies with long skirts and parasols would watch from grassy bluffs the Herculean efforts of men and machines to claw a canyon into the earth's surface. There was much noise down below, but no confusion, only the continuous motion of drilling, blasting, shoveling and dirt hauling. The Cut, called Hell's Gorge by one steam-shovel operator, was never silent and always hot and dusty, except when torrential rain turned the dust to mud and threatened to trigger yet another landslide.

While the work went ahead on the canal, a distinct class system emerged on the Isthmus, delineated by race and defined by the pay system which issued wages to the skilled whites in gold currency and to the unskilled blacks in silver currency. Living accommodations also reflected a person's “gold” or “silver” status. Simple barracks were built for the black workers and food was provided in mess kitchens. However, most of the West Indians did not like the food or the regimentation of barracks life, and many opted to live in ramshackle huts in the jungle. Their living conditions appeared deplorable but were in fact better than what many of them had known before coming to Panama.

Those on the gold payroll lived in while clapboard buildings with screened porches and manicured lawns. These buildings were divided into two or four apartments, each fully furnished and fitted out with plumbing, electricity and other conveniences, all at government expense. The size of a gold worker's apartment was determined by his salary, which entitled him to one square foot per dollar of monthly pay. To encourage married men to send for their families, wives were also entitled to one square foot per dollar of their husband's monthly pay. The top salaried, married men lived in detached houses, while single men lived in one of the bachelor hotels, usually sharing a room with another man.

The average pay for white workers was $87 per month (today $9,500.00 using the unskilled wage inflationary rate), plus free housing and medical treatment. A young graduate engineer was paid $250 ($27,300.00 — CPI calculator) to start, while a steam-shovel engineer received $310. The annual salary paid to Goethals was $ 15.000, half of what Stevens had made. These were generous salaries, but no one person or company grew rich building the canal. Salaries were set, there were no commissions, and the only work contracted out was the construction of the gates (which was handled by a Pittsburgh bridge builder), the manufacture of electric motors by General Electric and of steel parts for the lock walls and gates, which kept 50 mills, foundries, machine shops and specialty fabricators busy in Pittsburgh.

As the years went by, the work gained momentum. Everyone took pride in their efforts — they were seeing results and knew they were working together to build something of great significance. They were making history, but the monumental task they faced no longer felt like a war. In fact, most everyone seemed to be having a good time.

The American families living in the Canal Zone enjoyed a strangely care free lifestyle. One in which their basic needs and recreational pursuits were taken care of by the Commission. A friendly atmosphere and strong sense of community prevailed, along with an abundance of clubs and fraternities. Baseball fields had been built and leagues organized during Stevens' tenure, and other popular events included Saturday night dances, Sunday afternoon picnics and weekly band concerts.

Life in fact appeared to be too good to some visitors, who saw the place as some sort of socialist utopia where workers were so completely taken care of, critics wondered how they would adjust to the real world when the canal was completed and they returned to the United States. Others were concerned that the Canal Zone would become a breeding ground for political activists sold on socialism. Yet the zone was anything but political. with the people living there having no say in how things were run and their government located 2,000 miles away in Washington.

In 1912 the Gatun Dam was completed, causing water in the Chagres River to back up and overflow its banks, submerging the lower Chagres valley and creating a great artificial lake. As the basin slowly filled, animals fled to high ground and native villages were relocated.

Despite set backs from slides and floods in the Culebra Cut the work proceeded day and night. As dry excavations in the Cut neared completion. Goethals decided to finish the work with dredges doing wet excavation. The rail tracks in the Cut were taken up and all equipment removed. Then, with the workers all assembled at Gamboa at the north end of the Cut, a charge was set off to remove the dike holding back the Chagres River. and its waters flowed into the Cut.

The Canal's historic opening day finally arrived on August 15, 1914 two weeks after World War I began in Europe and 10 years after the United States had taken over the project. The Canal was ready for its first official vessel, and although there were numerous dignitaries on hand who were eager to go through on the first ship, Goethals decreed that only Americans who had worked at least seven years on the Canal would enjoy that privilege. A group or them and their families boarded the S.S. Ancon and entered the canal from the Atlantic. They were lifted up in the locks and transported across Gatun Lake before entering the Cut where their vessel traversed the Continental Divide, passing between Gold Hill and Contractors Hill. By this point most of them were in tears. The boat was then lowered back down to sea level in the Pedro Miguel and Miraflores locks, where it was set free to sail into the Pacific Ocean. The world's greatest shortcut was finally complete.

The Panama Canal was an American success story. Built under budget (total cost: $336.650.000 and ahead of schedule, the canal was the “moon launch” of the early 20th century. The massive locks, which raise and lower up to 14,000 ships a year (24/7/365), have worked with the precision of Swiss watches, and the canal now handles more annual vessel traffic than was ever envisaged by its builders. To this day, a more efficient means of digging the canal could not be applied. Many of the talented men who worked on this engineering marvel went on to other projects, most notably the building of railroads in South and Central America, northern Canada and Alaska.

In 1921, after years of seeking redress, Colombia finally recognized the independence of Panama upon receiving financial compensation from the United States in a lump sum payment of $25 million dollars. In 1939, the United States agreed to increase Panama's annuity to $434,000, an amount increased again in 1955 to $1,930,000. The United States also undertook to build a high-level bridge at the Pacific entrance to the canal, compelled in 1962 and called the Bridge of the Americas.

There remained, however, ongoing grievances on the part of Panama, which sought greater control over the canal. In 1977 under the Carter administration, a new treaty was signed which ceded the Panama Canal Zone, now called the Canal Area, to Panama under joint U.S.-Panamanian control until the year 2000, at which time Panama would assume full control. A separate treaty guarantees the permanent neutrality of the canal. When Colonel Manuel Noriega, a known drug smuggler who had seized military control of Panama, gained the country's presidency in December 1989 and declared war on the United States, an American military force of more than 25.000 soldiers attacked Panama City (Operation Just Cause) and forced Noriega's surrender. Panama's legitimately elected president was sworn into office during the American invasion and Noriega was taken to the United States to face charges of drug trafficking. Found guilty, he remains in a Florida prison.

Politics have always plagued Panama. When the Canal was officially handed over to Panama at the close of the 20th century, President Clinton chose not to attend the ceremony, his absence underlying the ambivalence of the American people regarding the U.S. withdrawal. However, despite initial misgivings concerning efficiency and maintenance of the canal, it continues to thrive.

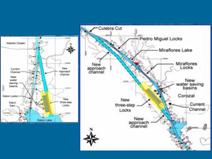

Improvements to operating machinery and in the form of widening, deepening and straightening have increased the Canal's capacity. Lighting has been added to the Culebra Cut to facilitate navigation at night. Ports have been expanded, and large infrastructure projects have transformed much of the Canal Area. Meanwhile, this rapid growth has drawn the attention of World Monuments Watch, which cites development pressures and lack of regulations as a threat to the region's tropical rainforests. With construction underway for a new third set of locks to accommodate larger ships the canal will continue to grow as an important transshipment and cruising destination as cruisers come to view this engineering miracle and one of the seven wonders of the modern world. |

|

President Roosevelt set a non-stop pace during his tour of the Canal in 1906. Here he is sitting at the controls of a 95-ton Bucyrus steam shovel. |

|

The SS Ancon marked the official opening of the Canal in 1914. In this photo you can see the ship being pulled by for electric locomotives (mules) as it makes it way north through the Pedro Miguel Lock. Click here to view a photo of the original mule. |

|

Today the Panama Canal is operated by the Panama Canal Authority (ACP — La Autoridad del Canal de Panamá). ACP is the agency of the government of Panama responsible for the operation and management of the Panama Canal. The ACP took over the administration of the Panama Canal from the Panama Canal Commission (the joint US-Panama agency that managed the Canal) on December 31, 1999, when the canal was handed over from the United States to Panama as the Torrijos-Carter Treaties dictated. The Panama Canal Authority is established under Title XIV of Panama’s National Constitution, and has exclusive charge of the operation, administration, management, preservation, maintenance, and modernization of the Canal. It is responsible for the operation of the canal in a safe, continuous, efficient, and profitable manner .

The Panama Canal has flawlessly served the world for ninety-six years by allowing for the quick and efficient transport of materials and goods. It has saved countless ships almost 8,000 nautical miles on trips from Asia to the East and Gulf Coasts of the United States and Europe. This has not only saved time, but fuel, resulting in less expensive goods at the store. The next time you go to an auto dealer, Costco, Wal-Mart, K-Mart, Best Buy or any other big box store think off how much more expensive those automobiles, TVs, toys and clothing items would be if the manufacturer had to add in the costs for the extra shipping mileage. This also applies to materials such as oil, steel and cement, the basic building materials of our modern world. |

|

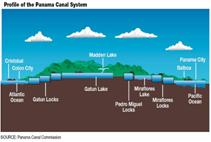

Profile of the Panama Canal. Click photo to enlarge. |

|

Future expansion plans for the Canal. Click photo to enlarge. |

|

The Canal has also contributed to our national security by allowing our Navy to move its ships from ocean to ocean in less time and at less cost. This was one of President Theodore’s main reasons for supporting the Canal. Building the Canal also contributed to the stability and prosperity of Panama. Once a province of Colombia and suffering under a dictatorial government along with being plagued by poverty and disease, Panama is now an independent nation with a great source of income for years to come. As our guide, a native of Panama, told us our tour of the Gatun Locks; “He and his Panamanians thanked the United States for giving them their freedom and the know-how to run the canal and build their nation and their prosperity.”

In building the Canal the entire world benefited from the medical advances in combating the dreaded diseases of yellow fever and malaria. It was Dr. William Gorgas, a U.S. Army physician, who had combated these dreaded diseases in Cuba, who was able to convince the experts that the common mosquito was the culprit that was killing thousands of people every year. His techniques in sanitation and insect abatement led to the eradication of these diseases that had caused the deaths of almost 22,000 French and 5,600 American workers attempting to build the Canal along with countless Panamanians each year.

The Canal was built in an era of American exceptionalism, an age where we believed we could accomplish great works for mankind. Our most respected people were our inventors, financiers, engineers and architects. Young people were motivated to go to school to study these professions so they could make contributions, not journalism and political science, hoping to change the world.

With the ongoing expansion of the Canal more and larger ships will be able to transit the Isthmus carrying greater loads of goods and passengers. This will keep the costs of trans-shipment from ocean to ocean low, benefiting the consumer. Like our interstate highway system the Panama Canal has been an unmitigated success and one of the greatest engineering achievements of the twentieth century, truly one of the seven wonders of the modern world. |