|

Vol.3, No 9, October 2010 |

|

If you are having problems viewing this page or the graphics please Click Here to view it in your browser or to visit our Blog Click Here. To view my Galleries of Geo-referenced photos from around the world Click Here. To view additional galleries Click Here. |

|

To remove your name from our mailing list, please click here. Questions or comments? Email us at fhenstridge@henstridgephotography.com or call 951-679-3530 To view as a Web Page Click Here. Please visit our Web Site at http://henstridgephotography.com. © 2009 Fred Henstridge Photography All Photos, Images, Graphics and Text are the copyright of Fred Henstridge Photography. All Rights are Reserved. |

|

Panama lays on an east-west axis even though it is the land bridge between North and South America |

|

The path of shipping through the Panama Canal |

|

Damage caused by one of the frequent slides in the Culebra Cut |

|

I have added an archive of all past editions of the Aperture. You can access this archive by clicking here. |

|

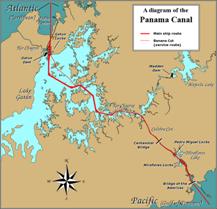

Course of the Panama Canal through the Isthmus of Panama |

|

Looking southeasterly through the Bridge of the Americas at the Pacific Ocean at sunrise. |

|

We were following a car carrier into the Miraflores Locks |

|

Panamax Container Ship lifted to the Level of Miraflores Lake |

|

SS Ryndam entering the second stage of the Miraflores Locks |

|

Clearing the medical emergency at the Miraflores Locks |

|

The infamous Cucaracha Slide on both sides of the canal delaying the Canal’s Completion |

|

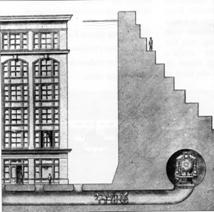

Past and Present cross-sections of the Culebra Cut |

|

Entering the infamous Culebra Cut |

|

All of the locks have double sets of gates for safety of the canal and the ships |

|

One of the many hilltops that survived the flooding to create 164 square mile Gatun Lake. |

|

The mitered locks gates |

|

The mile towing the Ryndam through the Gatun Locks |

|

The Radiance of the Seas being raised in the first stage of the Gatun Lock |

|

Giant overhead cranes were used to pour concrete |

|

Waiting for our catamaran at Gatun Lake |

|

An Eco-cruise boat plying the waters of Gatun Lake |

|

the Hotel Melia Panama, once a part of the School of the Americas |

|

Neotropic Cormorants flocking at Gatun Lake. |

|

Radiance of the Seas at the Colon 2000 Pier |

|

Most people know what the seven wonders of the ancient world are, but do you know what the seven wonders of the modern world are? According to a list compiled by the American Society of Civil Engineers the seven wonders of the modern world are:

2. The CN Tower 5. The Itaipu Dam — Brazil/Paraguay boarder 6. The Netherlands North Sea Protection Works

According the ASCE each one of these structures was selected for its contribution to the science of civil engineering and the construction efforts to build it. None of those listed, however, cost more lives to build and created more benefit to science, medicine and the global economy than the Panama Canal. I believe it is the greatest of these wonders.

I have seen the CN Tower, Golden Gate Bridge and the Itaipu Dam and now I can add the Panama Canal to this list. Once you transit this marvel of planning, engineering, construction and operation I think you might agree with my assessment of its ranking.

I transited the Panama Canal aboard the Royal Caribbean Cruise Line ship the Radiance of the Seas on October 3, 2010 as part of a fifteen day cruise from San Diego, California to Tampa, Florida. Our ports of call during the cruise were: Cabo San Lucas, Acapulco, Huatulco Mexico, Puntarenas Costa Rica, the Panama Canal (Colon), Cartagena Colombia and Georgetown in the Cayman Islands. In this newsletter I will focus on the Panama Canal as I have several blog entries describing our adventures during the cruise. If you would like to follow our daily activities and read some of my comments about the cruise and the ports we visited click here to read my first day’s post and then each succeeding day |

|

This will, by necessity be a three part story. Part one will cover some of the Canal’s technical details along with my personal experiences transiting the Canal. Part two will deal with the Spanish and French efforts to navigate and construct a transisthmian canal. Part three will tell the story of the American efforts to build the Panama Canal. I hope you will find all three parts entertaining, interesting and informative. Having said that let’s get on to the story of one of the seven wonders of the modern world — the Panama Canal

Before we begin our story I have to get one certain geographic detail cleared. The Isthmus of Panama, while connecting North and South America lays on an east-west axis. The Panama Canal cuts through the Isthmus in a general northwesterly direction from the Pacific Ocean to the Atlantic Ocean (Caribbean Sea). This means that the Bridge of the Americas at the Pacific end is about a third of a degree of longitude east (24 miles) of the end near Colon on the Atlantic (Bridge of the Americas: E 79° 33’ 58”, Colon :E 79° 55’ 10”). I know this may seem odd as we tend to view the Pacific Ocean west of the Atlantic. (This means that from the Bridge of the Americas the sunrise will appear over the Pacific Ocean.) Also The Pacific side sea level is about 20 centimeters (8-inches) higher than that of the Atlantic side due to differences in ocean conditions such as water densities and weather conditions. The total rise of the Canal from the Atlantic to Gatun Lake is 25.9 meters (85 feet).

Beginning at Balboa, on the Pacific side, there are three sets of locks raising ships to the level of Gatun Lake and then lowering them again to the level of the Atlantic Ocean. These locks are: Miraflores, at two stage lock raising a ship to 16.5 meters (54 feet) to the level of Miraflores Lake; Pedro Miguel Lock, a single stage lock, rising another 9.5 meters (31 feet) to the level of Gatun Lake; and Gatun Locks, a three stage lock lowering a ship back to the level of the Atlantic Ocean. Connecting these systems of locks is the 12.6 kilometer (7.8 miles) Culebra Cut (also referred to as the Gaillard Cut) transversing the Continental Divide and the 164 square mile Gatun Lake. The official stated length of the navigation along the Canal is 48 miles and the total transit time takes from 8 to 10 hours. The Canal operates 24 hours a day every day of the year.

We arrived at the Pacific entrance to the Canal about 4:30 a.m. on October 3, 2010. After a two hour wait to board the pilot and get in line we finally proceeded into the canal at the Balboa, passing under the Bridge of the Americas and by the docks at La Boca, just as the sun was rising. We had already received our “slot” assignment so we did not have a long wait like some of the other ships.

The upper decks of our ship, the Radiance of the Seas, was lined with passengers anxious to get their first look and the Panama Canal so it was a bit difficult to squeeze into an open space to shot my pictures, but as always I managed to get an advantageous location. Our speed through the Canal was no more than 4 or 5 knots per hour so we had plenty of time see everything. Things were going smoothly and the weather so far was pretty good. I knew it would not stay that way. As we were in the tropics and the rains would come, as they did every day from June through December.

It took about twenty minutes to approach the Miraflores locks, the first set of locks we would encounter in our transit. These southernmost double locks can have the biggest lift of any of the canal locks because of the extreme tidal fluctuations of the Pacific Ocean. The maximum lift for these locks can be as much as 65 feet at low water (they are rated at 54 feet). The Miraflores lower lock gates are the heaviest and the largest built to accommodate the Pacific tides: each gate weighs 745 tons and is 82 feet high. Depending on the state of the tide, this lift can be the largest in the canal (up to about 38 feet) or the least (at about 18 feet). A viewing platform at Miraflores gives visitors a chance to see the locks in action, and is especially busy on Sundays. There is a swing bridge at the south end of the locks which was opened in May 1942 and provided cars and trucks with a permanent way to cross the Canal. |

|

We were following a car carrier into the Miraflores locks so we had to keep a distance and travel slow. It was explained, in a video shown on the ship, that car carriers were the most difficult ships to navigate the Canal. This is due to their riding high in the water due to their relatively light load. They are prone to lateral rock so the pilots have to be very careful moving them in and out of the locks and crossing Gatun Lake.

We were being followed by a Holland America cruise ship, the Ryndam, as we entered the eastern lock. Once we in the lower level of the lock we stalled to a medical emergency aboard our ship and the Ryndam entered the western lock and proceeded to pass us and stay ahead for the remainder of the transit. The medical emergency was that an elderly man slipped and fell in Windjammer Café and evidently broke his hip. He had to be evacuated to a hospital in Panama City where he received medical attention. We latter heard he was doing fine and would be sent home, his cruise was over.

While we are waiting for the medical emergency to clear it might be a good time to mention the costs for a Canal transit. Tolls for the canal are decided by the Panama Canal Authority and are based on vessel type, size, and the type of cargo carried. For container ships, the toll is assessed per the ship's capacity expressed in twenty-foot equivalent units or TEUs. One TEU is the size of a container measuring 20 feet (6.1 m) by 8 feet (2.44 m) by 8.5 feet (2.6 m). Effective May 1, 2009, this toll is US $72.00 per TEU. A Panamax container ship may carry up to 4,400 TEU. The toll is calculated differently for passenger ships and for container ships carrying no cargo (“in ballast”). As of May 1, 2009 the ballast rate is US $57.60 per TEU. So for a ship carrying 4,000 TEU containers the toll would be $28,800.

Passenger vessels in excess of 30,000 tons (PC/UMS), known popularly as cruise ships, pay a rate based on the number of berths, that is, the number of passengers that can be accommodated in permanent beds. The per-berth charge is currently $92 for unoccupied berths and $115 for occupied berths. Started in 2007, this charge has greatly increased tolls for such vessels Passenger vessels of less than 30,000 tons or with less than 33 tons per passenger are charged on the same "per-ton" schedule as freighters. Our ship, the Radiance of the Seas, is listed at 90,090 tons with 2,501 berths. This would mean that if the ship was full the toll would be $ 287,615. We were informed, over the public address system as we transited the Canal, that our toll for this passage was $287,000 as the ship was not completely full. For Kathy and I this meant we had to contribute $230 to this transit. We were also told that the Ryndam was paying $197,000 and the car carrier was paying $80,000. I don’t how the toll for the car carrier is calculated, but I imagine it is by tonnage. Small vessels, such as private yachts are calculated on a sliding scale based upon the length of the ship, e.g. the toll for a ship up to 50 feet in length would be $1,300. If you are planning to take your little speedboat through the Canal you should be prepared to shell out $1,300 dollars. On October 7, 2007, the Norwegian Cruise Line’s Norwegian Pearl broke the toll record, paying $313,000 to transit the canal. The lowest toll ever charged was 36 cents, paid by Richard Halliburton when he swam through the canal in 1928. Swimming the Canal is no longer allowed. |

|

Once the medical emergency was cleared we were able to pass through the two stages of the Miraflores locks to the level of the Miraflores Lake, at 54 feet above mean sea level. The small depression between the Miraflores and Pedro Miguel locks became an intermediate lake and was planned as a temporary anchorage. Although ships occasionally do anchor here, almost all traffic continues straight on. A filtration plant is located here, supplying drinking water for the city of Panama. The lake is about a mile and a half long and half a mile wide.

Our next lock on our transit of the Panama Canal would be the Pedro Miguel lock. Pedro Miguel is about a mile and a half from Miraflores Locks, separated by Miraflores Lake, and is a single lock. It is unique in that the lock lift here is 31 feet as opposed to 28 feet at each step of the Gatun Locks and 27 feet each (without tide consideration) at the two steps at Miraflores. The additional water volume from this lock is discharged over the spillway at Miraflores. The terrain at Pedro Miguel and Miraflores is not open, like that at Gatun, so during construction a suspended cableway wasn’t possible for the pouring of concrete. Instead the engineers used enormous cantilever cranes, so large they could be seen from miles away, which could move about on tracks inside the locks and were used to pour 2.4 million cubic yards of concrete.

Until the late 1800s, concrete had been little used in building, and then mostly for floors and basements. There was still a great deal to be learned in the science of concrete production, which requires specific, controlled measurements of water with cement and sand. The concrete work in Panama was an unprecedented challenge that would stand unequalled in total volume until the construction of Boulder Dam in the 1930s. So much cement was used, George Goethals (the chief engineer), estimated saving $50,000 ($1.26 million in today’s dollars) just by shaking out each bag. In spite of the newness of the science the results were extraordinary. After nearly a hundred years of service the concrete of the Canal’s locks and dams remains in excellent condition, a fact regarded by modern engineers as one of the most astounding aspects of the entire Canal.

It took about twenty minutes to pass through the Pedro Miguel Lock and be elevated to the level of Lake Gatun at 85 feet above mean sea level. Three locks are used at each end of the canal (rat her than one or two) to provide a wide margin of safety. A single lock holding back a 130-foot-high head of water (depth of channel plus 85·foot height of Gatun Lake) would be dangerous. If the gates ever gave way, through a fault in the structure or by a ship collision, the results would be catastrophic for the ship, those on board, and the entire canal. The risks of gate failure are greatly reduced by having three locks and each with the added precaution of double gates.

The gates, the canal's most dramatic moving parts, swing like double doors, closing in a shallow “V” with the pressure of the rising water helping to seal the gates. The gates weigh several hundred tons each but are nearly weightless in water due to the lower half being a hollow watertight compartment. Not only does this greatly reduce the strain on the gate hinges but requires only a small 40 horsepower electric motor to open and close each gate leaf. The leaves are 65 feet wide by seven feet thick. However, they vary in height from 47 to 82 feet, depending on their position. The lower gates of the Miraflores Locks are the highest due to the extreme variation of Pacific Ocean tides. |

|

Water flooding the first stage of the Miraflores Locks |

|

Diagram of the double locks |

|

Once we passed through the Pedro Miguel Lock the rain began and we entered the notorious Culebra Cut. This nine-mile section from the Pedro Miguel locks to Gamboa, on the banks of the Chagres River, was the main engineering challenge throughout 40 years of construction effort by the French and Americans. Culebra, meaning snake, referred to the Rio Obispo valley north of Gold and Contractor Hills and represented the best pass across the Continental Divide from Gamboa to the Pacific. The actual saddle of the Continental Divide would today be, approximately on a line between Gold Hill and Contractors Hill. Water north of this point drained into the Atlantic Ocean and south of this point all water drained into the Pacific Ocean.

Culebra Hill itself is an ancient volcanic core of solid basalt and the valley soil is all unstable mix of granite, sedimentary rock, shale and many forms of clay which had the tedious ability to stick to everything — especially shovels. The clay when wet, however, would turn into a substance like putty or peanut butter and could flow like a glacier down the slopes and bury months of work in just a few days. The worst of these gravity slides occurred just south of Gold Hill at Cucaracha where, on one occasion in 1907, 500,000 cubic yards slipped into the canal. Miles of track were lost in such slides and steam shovels were buried so deep that only the lips of their cranes were visible. By 1912 Cucaracha had dumped some three million additional cubic yards of material into the canal, all of which had to be removed.

Break slides were even more destructive. These resulted when unstable rock formations lost the lateral support of earth that had been excavated. The first sign would be cracks in the ground along the rim of the cut. What was so unnerving about these slides was there was no telling when the next one would occur. It might be weeks, months or even years before an entire slope suddenly collapsed — often in a matter of hours. The worst of these break slides was on the west bank of the cut where some six million cubic yards of earth dropped into the canal during the summer of 1912.

Work along the bottom of the cut was hell. In the dry season, temperatures were usually in the range of 100 degrees Fahrenheit; in the wet season everything was mud. The noise of steam shovels trains and blasting was deafening. More dynamite was used during construction of the canal than in all previous wars of the United States combined, and many workers were killed by premature detonations, one of which killed 23 men.

Since the completion of the canal, the Culebra Cut has been widened in straight sections from 300 to 500 feet, and further increased to 600 feet in 2002. The cut is also widely known as Gaillard Cut, named in honor of the Central Division's Chief Engineer, David du Bose Gaillard. In 1913, Gaillard suddenly became incoherent while on the job and, upon returning to New York, died of a brain tumor a few months later.

Every ship and boat transiting the Panama Canal requires a pilot, and large ships will often have two on board throughout their lock transits. Pilots normally board the ship near the ocean entrances — at the breakwater near Colon on the Atlantic side and at the end of the channel near Naos Island on the Pacific side. The ship's captain and the pilots work together, but it's the pilot who gives the helmsman all navigational orders. While in the locks, the pilot is in constant contact by radio to the locomotive operators and, working in tandem with the ship's captain, tries to ensure the ship does not "touch" the side walls of the locks. (You can usually see the pilot and captain on the bridge wings at this point.) Even the slightest jar to the ship's hull against the concrete walls will scrape off chunks of paint, adding an extra cost to the already expensive Panama transit. When we reached the pier at Colon I noticed our ship had several fairly large “nicks” on the hull near the water line. This was pretty amazing as our lateral lock clearance was less than 6 inches and that’s awfully narrow for a 90,000 ton cruise ship. |

|

Repairing a slide on the slopes of the Culebra Cut |

|

With the help of a laptop computer, electronic charts and the Global Positioning System (which works by satellite), a pilot can tell exactly where the ship is throughout its transit of the canal. The Maritime Traffic Control Center in Balboa sends information about all ships in the canal to the pilot's computer, allowing him to view a "live" map showing the position of all transiting vessels. The pilot can easily find out the time and meeting point with other vessels. Pilots can also monitor the ship's speed, and distances to the canal banks, to other vessels, and to the locks. To accomplish such precision with the GPS they would need to be using differential GPS with numerous shore survey stations to provide the centimeter accuracy of the positioning. This is a terrific integration of mapping and GPS for ship navigation, that if had by the Exxon Valdez they would not have spilled all that oil in Alaska.

As we were transiting the Canal the pilot was giving us a running narrative over the ship’s public address system providing us with canal facts and history of the canal. Many passengers did not pay too much attention to these announcements, but I found them interesting and informative. I was also using a GPS attachment on my Nikon so I could plot the position of each photo I took during the transit.

After about an hour of traversing the Culebra Cut we arrived at the Chagres River and Gatun Lake, one of the most spectacular and ecological features of the Panama Canal. In 1912, upon completion of Gatun Dam, the Chagres River began to slowly fill its valley. It took almost two years for the water level to reach its planned height of 85 feet above sea level. With the new Gatun Lake covering an area of 164 square miles, equal in size to Barbados, Gatun Lake became the largest manmade lake in the world and it extended from Gatun to the Pedro Miguel Locks — a distance of 32 miles. Dozens of small villages vanished and scores of small islands were created. The world now contains more than 30 manmade lakes larger than Gatun Lake, but it was over 20 years before it had to give up its title.

When the lake first started to form, Canal workers warned local natives of the dangers but many refused to leave their homes and eventually had to be evacuated. In one case, a flood caused a rapid rise and a police launch was sent to a house near Lion Hill. The house was nearly submerged in water and police approached an elderly native and his family resting in a cayuca moored on the roof. “Don’t you know that the lake is going to cover your house?” asked the anxious police. The old man, unperturbed, replied, "That's the same old story the French told my dad thirty years ago."

Damming the Chagres Valley greatly diminished the cost and effort of excavation north of the Continental Divide and it also tamed the wild "lion" that had been the nemesis of the French. With the dam in place, the Chagres could rage and flood all it wanted, for the additional water merely flowed into Gatun Lake, which might increase a foot or more in height but could easily be regulated at the spillway of the Gatun Dam. In addition to supplying the means for ships to cross the Isthmus, Gatun Lake ( and Madden Lake) provide for the electrical needs of the Canal, and drinking water for the cities of Panama and Colon.

To keep a close eye on water levels, ACP (the Panama Canal Authority) installed monitoring stations throughout the lake after the El Nino weather phenomenon in 1998 caused the worst drought in the history of the Canal.

Ensuring adequate water for the canal is essential, and increasing the capacity of the lake by making it deeper is one measure that has been taken in the past. The navigational channel in Gatun Lake has been deepened to reduce draft restrictions and improve water supply, and other measures include legislation defining the boundaries of the watershed to guarantee its conservation.

It was at Gatun Lake the Radiance dropped anchor allowing us to leave the ship, via tender, for the shores of the lake to join the buses that would take us to the Gatun Locks, where we could view our ship pass through these last three locks, from ground level, and to take an Eco tour of the lake. The weather was threatening, but it looked like it would hold long enough for us to enjoy these two shore excursions — it almost did.

After reaching the shore of the Gatun Lake Yacht Club and boarding our bus the trip to the Gatun Locks took a mere 10 minutes. Upon arriving at the lock we were escorted up about a mile of steps to the observation area, which was totally packed with other tourists. This did not work for me so I asked the official guarding the door if there was another vantage point I could go to for taking some unobstructed photos and she smiling said yes. She directed me down one level where the security people had removed a chain allowing us to walk out on the level of the top of the lock where there was another observation area, complete with bleacher type benches. I immediately eyed a good spot and made my way to it. Now I was ready for the Radiance to come through the Gatun Lock. The only problem was that I was now exposed to the rain, which immediately commenced. So much for my clever plan. I tried to get under as much shelter as I could find and wait for the Radiance to enter the lock. The rain abated for a bit, for which I was glad, and the Ryndam was now entering the lock, with the Radiance playing second fiddle in the rear. I would take the pictures of the Ryndam and pretend it was the Radiance as it would still illustrate my description of the lock. |

|

The Chagres River flowing into the Canal at the entrance to Gatun Lake |

|

The radiance of the Seas at anchor on Gatun Lake |

|

The Gatun Locks observation building |

|

The Holland America Ryndam entering the Gatun Locks |

|

Although the Gatun Locks is a unique triple set of locks and is the largest and longest set of locks in the world, it has many aspects in common with the canal’s other locks, such as the miter gates and operating mechanisms. Each lock is 110 feet wide, 1,000 feet in length and can hold a ship up to a maximum of 106 feet in width and 965 feet in length. Each also has the ability to section itself into a smaller lock depending on the size of the ship. The locks were built in pairs to accommodate passing traffic. One variation between the Atlantic and Pacific locks is the height of their gates. The Pacific side locks were built to accommodate a tidal range of 20 feet. Ships that existed in 1909, when the locks were designed, had plenty of room, but today’s large cruise ships clear the lock walls with mere inches to spare. The Radiance of the Seas claims a beam width of 105.6 feet, a length of 962 feet and a draft of 26.7 feet. From these dimensions you can what a tight fit it is for these large cruise ships. Believe me when I say our ship came through with only a few inches to spare.

The locks, whether on the Pacific or Atlantic side use water from Gatun Lake: no pumps are needed — the whole system is gravity-fed with lake water entering huge 18-foot - high culverts running the length of the center and side walls of each lock. The water leads into a system of cross-culverts under the lock floors to rapidly fill the lock. Each cross-culvert has five openings for a total of 100 holes in each chamber floor for water to enter or drain, depending on which valves are opened or closed. This large number of openings distributes the water evenly over the lock floor to control turbulence while the lock is being filled. When observing the filling operation all the observer can see is a slow, steady rise of the water in the lock.

All movement of water is handled by the operators in the red-roofed control building in the center of each of the locks. Here a control board with a waist-high working representation of the locks shows the operator, in real time, what is taking place. Everything that happens in the locks happens on the control board at precisely the same time. The switches to work the lock gates are located beside the representation of that device on the control board. To lift a huge ocean- going ship in a lock chamber, the operator has only to turn a small chrome handle. Another ingenious part of the system are elaborate racks of interlocking bars below the control board to make the switches mechanically interlock. Each handle must be turned in proper sequence or it will not turn. This eliminates doing anything out of order or forgetting a step, ensuring safe operation. In essence, its canal operation for dummies, and it was all thought of way back in 1909.

Whether you enter the Panama Canal from the Atlantic or Pacific side, your ship is raised by water which has already lifted two other ships through the two locks ahead of you. To save water from Gatun Lake, it is reused by draining into each successive lock, lifting a ship each time. At Gatun, each lock, is a 28-foot rise and it takes about 10 minutes to bring a ship up to the next lock in the system. For large cruise ships, 52 million gallons of water are used to transit the canal — equal to a one-day supply for a city of 100,000. For this reason the canal operators do not mind the 100 inches of rainfall Panama receives each year. To them rain is money.

One of the great innovations of the locks was the use of electricity in operating motors, valves, lock gales and the unique electric towing locomotives (known as mules) which help keep ships in position. Designed by Edward Schildhauer, the locomotives work on tracks built atop the lock walls. Operating at a speed of about two miles per hour with a towing pull of 70,000 pounds, these locomotives were specially designed to travel the 45-degree incline between the lock chambers. The original cost for each one was $13,000. Today, new mules cost $2 million each. |

|

Typical cross-section of a Panama Canal lock |

|

The red-roofed control building at the Gatun Locks |

|

During construction of the Gatun Locks, concerns were raised about the foundation on which the massive triple-lock structure would rest. Built with two million cubic yards of concrete, each 1,000-foot long lock is a huge structure which, if stood on end, would compare with the tallest buildings of the modern world. Even lying flat, as they do, the walls of the locks are taller than a six-storey building. Each lock floor is between 12 and 20 feet thick and the total length of the Gatun triple locks, including the center guide walls, is over a mile. If any uneven settling had taken place, the locks might have cracked but this hasn't happened. It’s amazing the quality of the work that was done under such rugged conditions over 100 years ago.

Numerous borings were taken in the area and it was found the underlying shale-like material was superb as a base for the locks. Chief Engineer Stevens said early in the construction that "if nature had intended triple locks there she could not have arranged matters better.”' It was crucial for the integrity of the entire canal that the bedrock extending from the Gatun Locks to the hills west of Gatun Dam be absolutely stable and impervious to water and this, fortunately, turned out to be the case.

It took four years to build the locks once the first concrete was poured at Gatun on August 24, 1909. There were four intense years of planning, preparing the site, building steel-and-wood forms to mold the thousands of tons of concrete, and organizing a complex overhead system of pouring the concrete into the molds. The sand came from Nombre de Dios and the gravel came from Portobelo, where a large crushing plant was built and where Sir Francis Drake, who died of dysentery in 1595, still lies offshore in a lead casket.

A small automatic railway brought the appropriable amounts of gravel, sand and cement to a location near the Gatun spillway where the concrete was mixed. When the concrete was ready to be poured, large buckets, carrying six tons of concrete were whisked upwards by an overhead cableway. Suspended 85 feet above the ground and travelling at a speed of 20 miles an hour, the buckets were raced to the locks and lowered to the men below who would evenly spread the concrete. The whole system — the gigantic cableway lowers and large steel forms — was on tracks and as the work progressed, the entire structure was moved forward.

We spent a little over an hour at the Gatun Locks before departing for our Gatun Lake Eco-cruise, which would depart from the Hotel Melia Panama, located on the northwest shore of the lake. The hotel was once a part of the Escuela de las Americas (School of the Americas) and has been transformed into a 5 star hotel providing elegant and comfortable facilities. Located on the banks of Lake Gatun and only 25 minutes from the Colón Free Trade Zone it features activities such as adventure tours, ecotourism; cycling, canopy tours, eco-walks or trekking to view the exotic and diverse flora and fauna.

We took our Eco-tour of the lake in a catamaran along with a group of other tourists, who were a part of the Radiance cruise. Due to the rain and overcast skies we did not see many birds; however, the slow, relaxing cruise along the shores of the exotic jungle was very interesting. We saw a few two-toed sloths sleeping high in the trees and a flock of Neotropic Cormorants flying about looking for food. Someone claimed they saw a Toucan, but somehow I missed it. This was no doubt my greatest disappointment of the entire cruise. I had wanted to get some good shots of tropical birds so I could print a few 16x20 fine art posters for the house. I did not have any luck in Costa Rica or Mexico so now I will have to go the San Diego Zoo to get my bird pictures.

Colon is the western (Atlantic) terminus of the Panama Canal. Built on a swampy island near the canal's Atlantic entrance, Colon is named for Christopher Columbus, although it was first called Aspinwall in honor of William Aspinwall (founder of the Panama Railroad). A fire in 1885 destroyed most of the city, which was rebuilt in the French colonial style. Many buildings from this period still exist. The city was often scourged by yellow fever, a situation that prevailed until sanitary work (enclosing sewers and paving streets) was completed by the Americans. Upon completion of the canal, thousands of international workers returned home and Colon - which had been a prosperous and cosmopolitan city - was plunged into a protracted economic decline as its elite and middle class citizens moved to Panama City and elsewhere.

In an attempt to revive investment, in 1948 the south east part of the city was turned into a Free Zone. Here traders from around the world buy and sell at wholesale and avoid paying taxes. This has made Colon the world’s second busiest free port after Hong Kong. With a population of 200,000, Colon is Panama's second largest city, but much of the population lives in slums. However, the Panamanian government has made the clean-up of Colon a priority in an attempt to reduce crime and poverty.

Terminal (Pier 6) is located in a suburb on the west side of Colon. The port facilities here include a shopping complex and access to local tours. The Colon 2000 pier (on the east side of Colon) is located just outside the Free Zone. This cruise terminal features a duty free mall, craft boutiques, an internet café lounge areas and restaurants. (An overhead walkway connects the terminal with the shopping complex.) Taxis can be hired at the terminal's central desk and prices are fixed. (The tourism taxis enter the port parking area once the cruise tours have left.) A taxi ride into Colon is about $3 dollars (U.S). Places worth visiting include the cathedral on Calle 5, and the restored Washington Hotel where you can enjoy lunch on the terrace while watching ships enter Limon Bay to commence a canal transit.

Our ship docked at the Colon 2000 Pier Terminal on the east side of the city. We arrived at the pier, after a 25 minute bus ride, from the Melia Panama Hotel and Lake Gatun. The buses drop you at the parking area just outside of the shopping area and then you have to navigate through the numerous street vendors and shops to get to the ship. This may sound like a ploy to force you into shopping (it no doubt is) but its fun to listen to the street vendors and walk through the shops. After all these folks are only trying to make a living by selling goods and services to the thousands of tourists who transit the Canal. Some of the items offered for sale are mere souvenir trinkets while others are higher end products. You can buy top of the line watches, jewelry, gems such as diamonds, emeralds and sapphires, crystal ware, polo shirts and of course Panama hats. I thought of purchasing a Panama hat, but thought better of it as I would probably never wear it. I am not a hat person.

This was a day well spent. As a retired surveyor and civil engineer I was fascinated with the Panama Canal, one of the greatest engineering accomplishments of the twentieth century. The sheer magnitude of this project is amazing and to think it was completed under budget and two years ahead of schedule. This is a lasting tribute to the engineers, surveyors, laborers, mechanics, doctors, and yes politicians who made it possible. It was built at a time in our history when we believed, as a nation; we could do anything we put our minds to. An age of invention, innovation, science, faith and capitalism, something we could use a little more of today. This Canal has served the world for almost 100 years without a hitch. It has saved billions of dollars in the transportation of goods around the world and contributed to opening markets everywhere. Just think of the additional cost for goods from Japan and China if the ships transporting them had to navigate the treacherous waters as they traversed the Drake Passage at Cape Horn, at the southern tip of South America to reach our East Coast and Europe. The Canal is certainly a true engineering marvel and world utility.

You can view a complete gallery of all the photos I took while on our 15-day Panama Canal Cruise by clicking here. The photos taken during the Panama Canal transit begin at number 336 I hope you enjoy them as much as I did taking them. When you view one of the photos and it has a hyperlink (shown in red) under the caption you can click on it to open a Google Map showing the exact location where the photo was taken. When traveling, I always use a GPS attachment on my Nikon cameras so I can document the position of each photo.

In the next edition of this newsletter I will cover the Spanish and French history of this great engineering marvel and you can find out how a medical doctor, an anti-Semitic journalist, an assassin’s bullet and a bloodless revolution were responsible for building the Panama Canal. I think you will find it interesting and informative. |